Some state governments, California, Washington and New York, in particular are forcing auto manufacturers to transition to zero-emission vehicles, i.e. electric vehicles, or EV’s. The Biden administration is also attempting to accelerate this transition using both carrots in the form of subsidies, and sticks; strict new EPA tailpipe emissions are said to be coming. Simultaneously, federal and state agencies are also pursuing green-energy policies that limit electricity generation from carbon fuels.

Now, a single gallon of gas contains enough energy to easily propel a mid-sized car at highways speeds for 30 miles. That’s a lot of energy, and we use a lot of gasoline in the USA. So, if we want to replace gasoline and diesel fuel with electricity generated from renewable resources, then it’s important to ask; how much electricity do we need; where will it come from; how will we distribute it; and can we realistically increase reliable, green-energy production to meet the goals and rules for EV sales? If we end up burning more fossil fuels to generate electricity to power EV’s, then there’s really no benefit to using EV’s in terms of reducing green-house emissions. And if we drive up demand for electricity without a simultaneous increase in supply, then energy prices will rise. That’s the basic law of supply and demand.

So, there are a lot of questions that I wanted answers to. I’ve tried to capture several months of my own research into this topic in a rather lengthy paper– Will the Lights Stay On?

The paper is largely devoid of editorial comments, and focuses on hard data, almost all of which comes from state and federal agency websites with links, or references to all of the data sources. However I do reach a conclusion which I’ll repeat here:

If the federal government follows California’s lead and mandates EV’s while simultaneously ridding the grid of fossil-fuel based electrical generation, then what’s likely to happen is: a less reliable grid; more expensive energy; higher transportation costs; and a lower quality-of-life for most U.S. citizens, especially those with limited means. That, and the lights go out.

The paper identifies several key problems with a rapid transition to EV’s and green-energy:

- We don’t have the ability to store wind and solar power for more than a few hours. So the grid becomes increasingly unreliable with increasing amounts of green energy.

- We don’t have the transmission-line infrastructure to move energy around. New energy sources can’t always be built near existing substations, for example. Proposed wind farms off the coasts of Oregon and Washington do not have high-capacity transmission lines to tie into where the power comes on-shore.

- The amount of energy generated and consumed in the US has been amazingly steady at 4000TWh for more than a decade. The industry isn’t sized for rapid growth, and prices will rise rapidly if we outrun our supply chains.

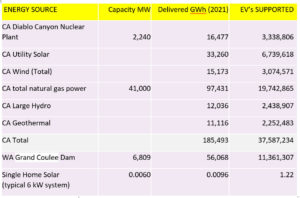

- For a sense of scale, if you took all of the output from Grand Coulee Dam, the largest generator of electricity in the US, it would power a little over 11 million cars. There are more than 36 million cars in California alone, and almost 300 million light vehicles in the US. So, if half of the cars in the US are converted to EV’s, then we’d need the equivalent of more than 13 new Grand Coulee dams, and we’d need them all producing electricity in about 10 years. That’s assuming we don’t shut down any more coal and gas generation.

- An EV uses almost half as much electricity as an average home if driven the same way as the gas car it replaces.

- It’s not clear that even local power grids are up to the task. You share a transformer with several of your neighbors. What happens when everyone in your neighborhood has an electric car, or two, and you are all trying to charge at the same time, as well as heat, or cool the house after a long day at work?

- The rate at which energy projects can be permitted and built is not well aligned with the rate of forced transitions to EV’s. Environmentalist and NIMBY interests will, as they always have, slow the rate at which millions of acres of land can be covered with solar panels, wind turbines and transmission lines.

- While not a focus of this paper, there are serious questions around charging station availability for those that park on the street, and even for rural interstate highway fueling stations.